19th century base ball player, private collection |

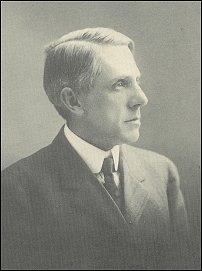

Ernest Lawrence

Thayer

|

Joslin Hall Rare Books News List presents-

19th century base ball player, private collection |

Ernest Lawrence

Thayer

|

Note: Most of the main players in the story of “Casey at the Bat” told differing versions of various parts of the story over the years, so piecing together the actual facts in some cases is a matter of picking which story seems most probable. We have assembled the following short history using two excellent references- ”The Annotated Casey at the Bat” by Martin Gardner (New York: 1967) and “Ernest Thayer’s ‘Casey at the Bat’, Background and Characters of Baseball’s Most Famous Poem” by Jim Moore and Natalie Vermilyea (Jefferson: 1994). We also want to extend thanks to Howard W. Rosenberg, who has provided invaluable suggestions and corrections, and runs a website devoted to "Cap" Anson and early baseball history.

Ernest Lawrence Thayer

|

Ernest Lawrence Thayer was born in Lawrence, Massachusetts on August 14th, 1863. Thayer, the son of a wealthy mill owner, was expected to go into the family business, and attended Harvard where he majored in philosophy and minored in humor. He wrote one of the annual Hasty Pudding Club plays and edited the Harvard Lampoon, Harvard's long-running humor magazine. While he was at Harvard Thayer became interested in baseball, and one of his best friends was Samuel Winslow, captain of Harvard’s baseball team. He also became friends with young William Randolph Hearst, who was the Lampoon’s business manager. |

San Francisco

After graduation Hearst's father put him in charge of the San Francisco Examiner, an ailing West Coast newspaper, and Hearst asked Thayer to write a humor column for the paper. Presented with the choice of writing humor columns for his school chum in San Francisco or managing family woolen mills in Worcester, Massachusetts, Thayer, rather unsurprisingly, packed his bags and headed for the West Coast. Thayer began writing anonymously for the Examiner in 1886, and by 1887 he was contributing humorous poetry to the Sunday edition under the name Phin. In February, 1888 he returned to the East and the woolen mills, but sent several more pieces to Hearst, including the poem “Casey at the Bat”, which was published on Sunday, June 3rd, 1888. Like most works of enduring genius, Thayer’s ballad was greeted with little fanfare, and it might have been quickly forgotten had not a writer named Archibald Clavering Gunter thought enough of it to clip the poem out of the paper that day and stick it in his wallet…

Fate

|

William De Wolf Hopper was a giant of a man, 6’2” with an athlete’s build and a deep, booming voice made for Shakespearian tragedy, but he chose to perform comedy instead, and was working for the McCaull Opera Company on Broadway in 1888. Hopper and his friend and fellow thespian Digby Bell were both confirmed base ball cranks, and persuaded their boss, Colonel McCaull, that the opera company should take advantage of a game between the visiting Chicago White Stockings and the New York Giants at the Polo Grounds for a day out and a bit of fun, and that they should then invite the ballplayers to their evening show. |

Hopper had wanted to include some special material for his guests, but wasn’t sure what to perform. Archibald Gunter, who was a friend of Hopper’s, suggested “Casey” and pulled the tattered column from his wallet. Hopper wasn't sure. His infant son was ill and he felt he could not concentrate enough to memorize such a long poem. But his son improved and Hopper, a seasoned professional, soon had the poem memorized.

The First Reading

| On August 14th, 1888, the Opera Company spent a festive day at the Polo Grounds watching “Cap” Anson’s White Stockings beat their Giants 4-2 (the same score the home team in "Casey" would lose by), and then everybody, including both ball teams, went back to the Opera House, where Prince Methusalem was the featured show. At the end Hopper walked out onto the stage and gave a stirring performance of “Casey at the Bat ”. |

|

“The audience literally went wild,” reported the New York World the next day- “Men got up on their seats and cheered… it was one of the wildest scenes ever seen in a theatre”. By odd coincidence, August 14th, 1888 also happened to be Ernest Lawrence Thayer’s 25th birthday.

Fame

The poem made De Wolf Hopper famous, and Hopper made the poem famous. By his own estimate he recited it 10,000 times over the next decade; it took him exactly 5 minutes and forty seconds each time. But almost nobody, including Hopper, had any idea who had written it. In the early 1890s Hopper was performing in Worcester, Massachusetts when he received an invitation to meet the author. Thayer and his friends entertained Hopper at a private club, and Thayer was persuaded to get up and give what Hopper would later recall as one of the worst renditions of 'Casey' he had ever heard. Hopper recalled- "In a sweet, dulcet Harvard whisper he implored Casey to murder the umpire, and gave the cry of mass animal rage all the emphasis of a caterpillar wearing rubbers crawling on a velvet carpet".

Hopper asked Thayer that evening who the inspiration for Casey was, and Thayer replied that it was his old Harvard chum, baseball captain Samuel Winslow. Thayer himself would later declare that there was no “real” Casey, and that the name and vague image of Casey were drawn from a bully who once threatened to beat him up in high school. Such mundane answers have, of course, never satisfied baseball fans, who have come up with any number of “real” Casey’s Thayer had in mind.

| “Kelly at

the Bat” Perhaps the most famous “real” Casey was Mike Kelly, baseball’s first real superstar and one of the finest players ever to grace the diamond. He wrote the first baseball autobiography, and performed on stage after his career was over. On July 28th, 1888, not two months after “Casey” had first appeared in San Francisco, the editor of the New York Sporting Times, who had noted a striking similarity between Casey and Kelly, published an “East Coast” version of the poem, with the first five stanzas removed and “Kelly” substituted for “Casey”. Kelly himself had great fun performing the poem on stage, and this altered version would give rise to later stories that the Sporting News version was actually the original. |

|

Author! Author?

And still, very few people knew who wrote it. Various guesses were made, and several claimants came forward. One popular theory was that Sioux City Tribune editor William Valentine had written it, and the first printing of the poem in an anthology, in 1902, attributed it at first to Joseph Quinlan Murphy. George Whitefield D’Vys of Somerville, Massachusetts, proved to be the longest-running, most troublesome imposter author, and a long and complex investigation played itself out in the journals and newspapers in 1908, making the poem even more famous. Controversy will do that. By the end of the decade Thayer’s authorship was fairly well established, and he offered an edited version to The Bookman for their January, 1909 issue. This appears to be the version Thayer preferred, though it is generally conceded that his editing did nothing to improve the poem, and he substituted the phrase “great Casey ” for “mighty Casey” in the last line! When all is said and done, the first, 1888 version, remains the best.

Posterity

"Casey" has spawned dozens of other poems, poems where Casey strikes out again, hits a home run, makes a comeback, and even takes the mound; eventually Mrs. Casey, Casey’s sister, and Casey’s daughter also get turns at the plate. In addition to these poems, the original "Casey" has been altered, both subtly and otherwise, many times in many printings over the last 100 years.

"Casey at the Bat" may not be great poetry, but it is a great poem, and for over a hundred years it has held our imaginations and hearts. There have been many explanations given. Certainly the most important factor is that Casey is expected to succeed, he has all the tools to succeed, and instead he fails. Marvelously, majestically, and with great verve, he falls flat on his face. Contrasts like this are the heart of comedy, and also the heart of baseball. The best hitters fail seven out of ten times, and each dramatic confrontation between batter and pitcher contains all the possibilities of great success or crashing failure. If baseball is, as some baseball writers have spent a lot of paper arguing, a metaphor for American life, then "Casey at the Bat" is a metaphor for all of baseball, the entire drama and pathos and history of the game neatly wrapped up in thirteen stanzas. And, most importantly, it's just plain funny.

For those seeking more information about "Casey at the Bat" and its author, I can recommend two excellent sources. "The Annotated Casey at the Bat" by Martin Gardner (New York: 1967) contains a very good short history of the poem and its author, as well as an important short bibliography of its early appearances. The heart of the book is a wonderful collection of early "Casey" poems and the poems that "Casey" spawned, from Grantland Rice's "Casey's Revenge" to " 'Cool' Casey at the Bat" from MAD magazine.

“Ernest Thayer’s ‘Casey at the Bat’, Background and Characters of Baseball’s Most Famous Poem” by Jim Moore and Natalie Vermilyea (Jefferson: 1994) is a thorough, detailed and entertaining account of Thayer, early baseball, and the poem. It is the best, most in-depth book on the subject of which I am aware.

-Forrest Proper, July, 2004

Early Printings of “Casey at the Bat”

(adapted from material in “The Annotated Casey at the Bat”

by Martin Gardner, with additional notes)The San Francisco Examiner, June 3rd, 1888. The first printing of the poem.

Harvard University, Class of 1885: Secretary’s Report No.V, 1900. pp.88-90. This is believed to be the first time the poem was printed in a book.

Casey at the Bat. New Amsterdam Book Co.: 1901. The first separate printing of the poem by itself. An illustrated promotional booklet; the poem is not attributed to any author.

|

A Treasury of Humorous Poetry. Frederic Lawrence Knowles, editor. Boston, 1902. The second printing in a book, and first anthology appearance in a book. In the first several binding states the poem is attributed to “Joseph Quinlan Murphy”. Why is unknown, because as far as anyone can tell, there was no poet or author by that name. Interestingly, in the third “state” of the book, also dated 1902, the publisher has gone to considerable trouble to reattribute the poem to Thayer, replacing two entire pages in the book with new inserted sheets, hardly an inexpensive change. This was around the time of the first serious investigations into the authorship of the poem. |

Casey at the Bat. New York, 1904. A booklet featuring De Wolf Hopper, with no authorship attribution for “Casey”.

| Casey at the Bat. Kansas

City: 1905. A booklet. States that the text was furnished by Thayer and approved by

Hopper. The Bookman. Vol.28, January, 1909. Thayer’s revised version, where he changes the last line to “Great Casey has struck out”. Ick. Casey at the Bat. Chicago: 1912. The first hardcover edition solely devoted to the poem. Illustrated by Dan Sayre Groesbeck. The Home Book of Verse. Burton E. Stevenson, editor. 1912. A corrupted version. |

|

A Printing I would Like to Own:

In 1935, at the 50th Anniversary of the Harvard Class of 1885, a banner read -

An Eighty-five man wrote

"Casey at the Bat"

The Epic of BaseballIn the evening as the men gathered for dinner a reprint of “Casey” was placed at each seat.

The Poem.

As it was first printed in 1888 in the San Francisco Examiner-Casey at the Bat

A Ballad of the Republic, Sung in the Year 1888The outlook wasn’t brilliant for the Mudville nine that day;

The score stood four to two with but one inning more to play.

And then when Cooney died at first, and Barrows did the same,

A sickly silence fell upon of the patrons of the game.

A straggling few got up to go in deep despair. The rest

Clung to that hope which springs eternal in the human breast.

They thought if only Casey could but get a whack at that-

We'd put even money now with Casey at the bat.

But Flynn preceded Casey, as did also Jimmy Blake,

And the former was lulu and the latter was a cake;

So upon that stricken multitude grim melancholy sat,

For there seemed but little chance of Casey's getting to the bat.

But Flynn let drive a single, to the wonderment of all,

And Blake, the much despis-ed, tore the cover off the ball;

And when the dust had lifted, and the men saw what had occurred,

There was Johnnie safe at second, and Flynn a-hugging third.

Then from 5,000 thoats and more there rose a lusty yell;

It rumbled through the valley, it rattled in the dell;

It knocked upon the mountain and recoiled upon the flat,

For Casey, mighty Casey, was advancing to the bat.

There was ease in Casey's manner as he stepped into his place;

There was pride in Casey's bearing and a smile on Casey's face.

And when, responding to the cheers, he lightly doffed his hat,

No stranger in the crowd could doubt 'twas Casey at the bat.

Ten thousand eyes were on him as he rubbed his hands with dirt;

Five thousand tongues applauded when he wiped them on his shirt.

Then while the writhing pitcher ground the ball into his hip,

Defiance gleamed in Casey's eye, a sneer curled Casey's lip.

And now the leather-covered sphere came hurtling through the air,

And Casey stood a-watching it in haughty grandeur there.

Close by the sturdy batsman the ball unheeded sped-

"That ain't my style," said Casey. "Strike one," the umpire said.

From the benches, black with people, there went up a muffled roar,

Like the beating of the storm-waves on the stern and distant shore.

"Kill him! Kill the umpire!" shouted some one on the stand;

And it's likely they'd have killed him had not Casey raised his hand.

With a smile of Christian charity great Casey's visage shone;

He stilled the rising tumult, he bade the game go on;

He signaled to the pitcher, and once more the spheroid flew;

But Casey still ignored it, and the umpire said, "Strike Two."

"Fraud!" cried the maddened thousands, and echo answered "fraud";

But one scornful look from Casey and the audience was awed;

They saw his face grow stern and cold, they saw his muscles strain,

And they knew that Casey wouldn't let that ball go by again.

The sneer is gone from Casey's lip, his teeth are clenched in hate;

He pounds with cruel violence his bat upon the plate.

And now the pitcher holds the ball, and now he lets it go,

And now the air is shattered by the force of Casey's blow.

Oh, somewhere in this favored land the sun is shining bright;

The band is playing somewhere, and somewhere hearts are light,

And somewhere men are laughing, and somewhere children shout;

But there is no joy in Mudville -mighty Casey has struck out.